Book Review

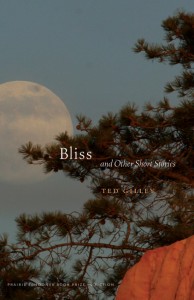

From within their overheated cars and unstable relationships, the characters in Ted Gilley’s debut collection, Bliss and Other Short Stories, contemplate a lost American Eden. The nine powerful stories in this book, which won the 2009 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction, gather unity from their characters’ sharp perceptions of forests and fields, strip malls and parking lots.

From within their overheated cars and unstable relationships, the characters in Ted Gilley’s debut collection, Bliss and Other Short Stories, contemplate a lost American Eden. The nine powerful stories in this book, which won the 2009 Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction, gather unity from their characters’ sharp perceptions of forests and fields, strip malls and parking lots.

History is understood by these characters through an eclectic amalgamation of westerns, family photo albums, and old radio programs. For example, in “White,” a couple sits in a car outside the Padres’ baseball stadium. The couple fights as they wait for the traffic to clear. In a lull, Sheila “gaze[s] out at the acres of cars and [thinks] of the television westerns she’d watched growing up back East: plains alive with restive, murmuring cattle, rain sifting from Technicolor skies.” While Sheila remembers the television program as being more compelling than the reality before her, Gilley situates the reader within her body. When her husband grabs her T-shirt, she wriggles out of his grasp and finds herself walking across the parking lot in just her bra, “lightly touching the hot hoods and trunks as if they were tumbled boulders along a path she wished to remember and would later retrace.” The story follows Sheila as she moves through the neighborhood. With every step she takes, the story alternates between physical experience and the strange current of Sheila’s thoughts.

In these stories, otherwise mild-mannered women often perform daredevil acts, while men seem acquiescent by design, as if Gilley is critiquing society’s expectations of masculinity. The title story begins: “All my life, I seem to have been mistaken for someone else.” People confuse Cleave, the story’s narrator, with others in supermarkets, at the pharmacy, and even when they pass him in cars as he walks to work. “I love you, Jamie!” one woman yells to Cleave. “Bliss” gains momentum not in the offices of the soon-to-be-bankrupt travel brochure publishing company where Cleave works, but instead on his walks with a female friend whom he fails to share his love. Cleave’s aching infuses the main character and the story with originality. On his way home, a disappointed Cleave stops to look at the moon. He says, “I lay down on the body of the dead earth and watched the rimed and frozen sky turn its back on the day, and my fingers and ears sang and stung with perfect, blissful pain.” Here, he takes on a transcendent quality. Cleave, like others in these stories, is worn by misfortune, and Gilley’s use of imagery makes these transformations credible.

Several stories in this collection show teenagers at their own crossroads. Thirteen-year-old Ginger in “Invisible Waves” attempts to define her limits by lying to her parents and sneaking out at night to get on the radio. Surprising even herself, she climbs to the top of a radio tower, where she “looks down on the flat roof of the radio station, its pools of water moving in the breeze like twitching sheets, and at the toy traffic going back and forth on the road down in front.” In comparison, sixteen-year-old Carl in “Physical Wisdom” finds himself unable to sleep in his house after an earthquake occurs shortly after his family relocates to California. He tries sleeping in a tent in the backyard but ultimately ends up in his mother’s studio, where he gazes at her painting of an angel sitting on Saint Matthew’s lap. Although the story builds on the image of the angel and the saint, Carl finds no quick or easy redemption. He does, however, get to know the city of Loma Feliz with its high school, bougainvillea-draped neighborhoods, and the ocean where “an occasional gull-screech cut through the steady roaring of the waves” and “the retreating water slurred and sucked” at his sneakers.

Short story writers, like Bobbie Ann Mason in Shiloh and Other Stories and Sherwood Anderson in Winesburg, Ohio, often make a region or a specific town the locus of all feeling. In comparison, the characters in Bliss and Other Short Stories share no one region, though their landscapes have come to bear some resemblance to each other through commercial development. Gilley maps contemporary America in ordinary towns on both coasts, and although his stories range in location, they pulse with his masterful attention to place, the poetry of his images, and the predicaments of lives no longer simple.

About the Reviewer

Rachel Bara recently earned an MFA in fiction from Pennsylvania State University. She lives in State College, Pennsylvania.