Book Review

In 1999—year of the rabbit; year before the Y2K bug; only a handful before the events of September 11th; before Al Queda, stateless, faceless, entered the common parlance of the home; well before the blue-tarp tents of Occupy’s spastic movement; before the blood-tide of mass gun violence we wade through stateside today—Paolo Virno asserted in Il Ricordo Del Presente that the contemporary experience of history was one underwritten by an unshakable sense of déjà vu. Using the pathology of memory as a framework for understanding historical culture and consciousness, Virno argues that the present generation has been obliged to become “spectators of their own actions…watching themselves live.” To live, that is, in a state of déjà vu, in which the future is closed, in which the subject is caught in the riptide of global flows entirely beyond control and rendered powerless. This condition seems to synchronize as well with ancient theories of irony. In the tradition of tragedy, an individual in the ironized position lives a life incongruous to reality. They live a life within a closed future. They are, first in ignorance, then in a state of sickening self-awareness, resolutely out of phase. The individual in the ironized position—much like the individual who experiences déjà vu, who is in and outside two noncoinciding times at once—is on some fundamental level severed from themselves. Set at a distance, apart from the immediate.

In 1999—year of the rabbit; year before the Y2K bug; only a handful before the events of September 11th; before Al Queda, stateless, faceless, entered the common parlance of the home; well before the blue-tarp tents of Occupy’s spastic movement; before the blood-tide of mass gun violence we wade through stateside today—Paolo Virno asserted in Il Ricordo Del Presente that the contemporary experience of history was one underwritten by an unshakable sense of déjà vu. Using the pathology of memory as a framework for understanding historical culture and consciousness, Virno argues that the present generation has been obliged to become “spectators of their own actions…watching themselves live.” To live, that is, in a state of déjà vu, in which the future is closed, in which the subject is caught in the riptide of global flows entirely beyond control and rendered powerless. This condition seems to synchronize as well with ancient theories of irony. In the tradition of tragedy, an individual in the ironized position lives a life incongruous to reality. They live a life within a closed future. They are, first in ignorance, then in a state of sickening self-awareness, resolutely out of phase. The individual in the ironized position—much like the individual who experiences déjà vu, who is in and outside two noncoinciding times at once—is on some fundamental level severed from themselves. Set at a distance, apart from the immediate.

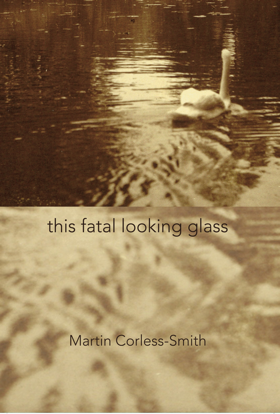

One voice most suited to address this schizophrenic contemporary state, this state of contemporaneity, must be poet Martin Corless-Smith, author of the new novel This Fatal Looking Glass (2015) from SplitLevel Texts. It is on these themes of contemporaneity as disjunction, displacement and self-exile in and out of time, that Corless-Smith’s new book meditates—themes initially introduced into his oeuvre by several of his previous publications, including Nota (Fence 2003) and Complete Travels (West House Books 2000). While these earlier works perform a cotemporal torquing across multiple times and lyric modes by formal and linguistically innovative means, the speaker in This Fatal Looking Glass—a novel eschewing linearity in favor of the fragment as its primary unit—reflects more broadly on the practice and consequences of contemporary art making. “As I was becoming unreal…” Corless-Smith begins, and continues from this point to trace through the novel the self-ironizing effects of the artist’s tendency to multiply worlds and selves. The work demonstrates how this impulse—toward forming image, narrative, and persona; toward making oneself contemporary and thereby rendering oneself resolutely out-of-phase—wholly displaces the artist from reality, or comes at least to threaten their reality. The world of This Fatal Looking Glass is a world of reflections, returns, fractures, and irony, set against the backdrop of contemporary London and along the city’s several rivers, which function as figurative images of flow, static, and eternal return.

The speaker in This Fatal Looking Glass is twice removed from reality, then—and knows it, and knows also the absurdity of having initially indulged this refraction. First, the speaker’s context is contemporary, a world of London bombings and global capitalism juxtaposed against a circulating vein of quotidian experience—their first context is, in other words, Paolo Virno’s closed future of the here and now. Their second context is a self-reflexive aesthetic one: the speaker in the novel, an artist, has come to realize that for all his efforts in art making, in being a contemporary poet and painter, he has wholly abstracted himself from reality, and from the ability to live unselfconsciously. For Corless-Smith (or rather, for his fragmented, fictional, thrice-Janus-faced narrator) the situation is compounded beyond Virno’s description. Having put himself out of phase (so that the lives of the Romantic poets become more real to him than himself), Corless-Smith’s speaker slides in and out of reality, self-ironized, self-fated, so absented from his own time that he has rendered himself unable to maintain meaningful relationships with his son, his ex-wife, his ex-lover.

Indeed, it is against this seminarrative, semiconfessional backdrop—against the backdrop of a tumultuous affair with a younger woman, followed subsequently by divorce and the failure of his precipitating love affair—that we find Corless-Smith’s narrator exploring the strange inevitability of his situation, having passed into a state of self-exile by, paradoxically, returning to his childhood town. It is the condition of this speaker, however, to live ironically in the knowledge that he has put himself in this ironized position—that, in some way, he wanted this exile, this shame, in order to enable him to write, to write the novel at hand:

It is noteworthy that his journal and his poetry often predicted, with unalloyed precision, events that would unfold sometimes 5 or 6 years later. A marriage. A son. An affair with a younger woman. Or perhaps just a series of clichés after all.

The novel’s devastating realization: that Corless-Smith’s narrator has invited his fall, which, hideously, is “not without a gain, as there is often some increase in awareness, some gain in self-knowledge, some discovery on the part of the tragic hero.” Above all, This Fatal Looking Glass remains rigorously self-aware, aware of its textuality and its sundry realities and unrealities, and the ways in which the events that have transpired to form its narrative have not only supported its existence, but were even invited to occur. At the root of this speaker’s unreality is his own hand. “But I have wanted this,” he writes. “The wrong choices willfully taken.” To enter into a lyric world of mirrors, where memory and self are mined for the purposes of poetry, is to have fated oneself to certain behaviors, even to certain doom. This fatal looking glass. The story of the narrator’s affair, fall from grace, and subsequent self-exile seems a parable of the risks of art making. Making oneself, through art, twice-contemporary is to see yourself seeing yourself:

With his love it had seemed impossible, as opposed to unavoidable. That it could not and should not happen, that it could not and would not work. It was a scream of fury outside of the home. A door slammed before his wife returns home. Yet how can she not hear it? And again it was all to begin a story. Or to see if others existed. To step into something ill-defined that was not appropriate, that was implausible and abhorrent, and therefore irresistible. It was not a victory of one scenario over the other, or the choice of one person over the other, it was simply a door peered through that had been cracked all along, and was found out to be curiously inevitable.

Here, the door the speaker peers through is somehow linked to marital deviance, but it can just as easily be aligned with deviances inherent to the making of a poem: “the poem is the subject floating into an object…, so that poet and poem come into being simultaneously.” At this yawing aesthetic wing-tip between subject and object, there is a “door of becoming opened at the boundary of selfhood.” To see yourself seeing yourself—is this not to be utterly yourself, while simultaneously occupying a position utterly beyond the self, in exile from all that is familiar? “Reflection,” writes Corless-Smith, “is consciousness.”

Let us return to the surface of a pond. Vastnesses reflected and supported. Consciousness withdraws from and overtakes the spoken. Half recalled, half read. Half imagined, half written.

It is this exile from the familiar that Corless-Smith explores throughout This Fatal Looking Glass, a novelistic collage of commentary, quotes, scenes, confessions, self-parodies, jokes, and dialogues. Oscillating between the banal and the grandiose, between egotism and self-castigation, Martin Corless-Smith offers a portrait of the artist whose art has displaced him from a time already displaced. In one sense, the search for the artificiality of narrative has resulted in an “apocalypse” of unreality. In another sense, the activity of self-displacement has positioned the narrator to “banish” himself so as to “join the element of otherness,” that state of pure desire, that purity in the erotic, deviant though it might seem. Throughout this novel of self-ruination, there gleam in selfhood cracks that might open to becoming’s light. But it is a bitter crucible to pass through, the same crucible of self and image and beauty’s image that prompted Wordsworth to ask at the banks of the river Wye: “Was it for this?” A question Corless-Smith echoes and echoes, Echo and Narcissus, both at once.

About the Reviewer

Kylan Rice has poetry published or forthcoming in The Seattle Review, Gauss-PDF, Inter|rupture, [Out of Nothing], and elsewhere. He is an MFA candidate at Colorado State University, where he produces the Colorado Review podcast. Contact info: rice.kylan@gmail.com