By Colorado Review Associate Editor Susannah Lodge-Rigal

I am a slow writer. This is something I know to be true: as a student at Colorado State University and in my writing life prior, I have never been quick to come up with new ideas for poems or essays. I admire poets who, day after day, produce writing—who resist veering from this daily procedure no matter what. And despite this admiration, I can’t count myself among them. While I am growing more comfortable with my own pace, I also have a thesis to write toward (eep!), and I hope to push myself and experiment so as to get to know my writer-self a little better. A professor I had in college would say, “The more you write, the more you write.” Of late, poetry procedures have been integral to writing more, even if that writing is often messy.

One of my hang-ups when approaching the page is a risk of failure: writing toward derivative, boring, or corny ends. Writing procedures have helped me jump the hurtle and just start writing; they are an entry point by which to enter that formidable white space and essay forth. And more than just getting started, these procedures have helped me think of poetry as play—an opportunity to take risks and enjoy the spontaneity and mystery of words. And while much of what I come up with is messy, I also feel better for having tried, having started. Sometimes, from the procedural compost I make, I am able to find the start of a new poem. Procedures have helped me see inspiration in unlikely sources: the TV shows I watch; the photographs that decorate my room; scents of candles, trees, old barns; street names; atlases; even the white space on the page itself. They have helped me enter into a kind of productive uncertainty regarding how I inhabit my own poems. In short, they help me find surprise (and sometimes nonsense) in my own words. Here are a few procedures I’ve been playing with in the last few months and a few I’m excited to try:

- •Write from a family myth or story.

- •Use a prose block from a previous writing project and perform an erasure (and then another!).

- •Turn to a page of a random book, point to a line, and use that line as a prompt.

- •Look at a framed photo—use both photo and frame as a prompt.

- •Try to write a poem in a received form, then break that form.

- •Write an occasional poem about an occasion that happens every day: taking a shower, brushing your teeth, walking to work, talking to your mom.

- •Write while listening to a song; pull five words from that song to incorporate into your writing.

- •Write a couplet every day before bed.

- •Speak words aloud while doing an activity that involves your hands (folding laundry or doing the dishes) and write down what you can remember.

- •Use a line from a sitcom as the first line of your poem.

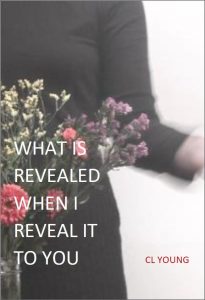

Often, procedural prompts allow me only an entry point—a way to access the page so as to venture toward whatever the heart of that poem truly is. But for me—a slowpoke poet—a starting point is often just the push I need. For the true “what’s what” on the marvel of procedural poems, check out recent MFA graduate C. L. Young’s chapbook, What Is Revealed When I Reveal It To You.