By Colorado Review Editorial Assistant Ben Greenlee

Not that being odd is currently under literary attack or anything, but I’ve been thinking about how certain pieces of writing are perfectly misshapen—a trapezoidal-peg-round-hole sort of thing—just enough to defy clear categorization. A wonderfully bearded colleague of mine from the Center for Literary Publishing wrote about personal aesthetics and how they may color a reading or writing experience (you really should check out his thoughts by clicking right here), while an equally wonderful colleague, though substantially less bearded, discussed his new immersion into contemporary fiction that moves away from traditional narrative (follow the trail, my friends). What they, and I, are ultimately discussing is the inherent joy in being challenged, of engaging with a text that defies in the most delightful of ways, that turns a knob in the deep machinery of us which then initiates a reply of, “Hey, what is this?”

Not that being odd is currently under literary attack or anything, but I’ve been thinking about how certain pieces of writing are perfectly misshapen—a trapezoidal-peg-round-hole sort of thing—just enough to defy clear categorization. A wonderfully bearded colleague of mine from the Center for Literary Publishing wrote about personal aesthetics and how they may color a reading or writing experience (you really should check out his thoughts by clicking right here), while an equally wonderful colleague, though substantially less bearded, discussed his new immersion into contemporary fiction that moves away from traditional narrative (follow the trail, my friends). What they, and I, are ultimately discussing is the inherent joy in being challenged, of engaging with a text that defies in the most delightful of ways, that turns a knob in the deep machinery of us which then initiates a reply of, “Hey, what is this?”

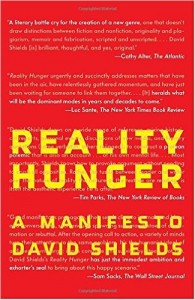

The answer is something akin to another question, “Does it matter?”—yet I’ve been asking these uroboric questions nonetheless, and it stems from the odd works that have crossed my path these past few months. Most notable would be David Shields’s Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, a collage-style piece of nonfiction which challenges the notion of traditional narratives found in any genre, and advocates for artistic plagiarism. This book is both personal and provocative and a little dirty (in a way that throwing sand in an opponent’s eyes during a schoolyard brawl is dirty). He wants to ruffle feathers or, perhaps more accurately, he wants to pluck the whole damn chicken, and while he’s no pied piper to my child-heart, I appreciate the risks he’s calling for, the ways in which he’s asking his readers to abandon all pretense of what is true and what is owned. His  manifesto is liberating like a really bad driver’s license photo is liberating: the image doesn’t need to be perfect, it doesn’t need to fit the expected, the image just needs to be you.

manifesto is liberating like a really bad driver’s license photo is liberating: the image doesn’t need to be perfect, it doesn’t need to fit the expected, the image just needs to be you.

Another odd book would be The Collected Works of Billy the Kid by Michael Ondaatje, a verse-novel which uses free verse vignettes to tell the story of the notorious outlaw. In my limited reading experience I’d never even heard of such a thing, verse-novel, yet I was immediately taken with the character and scene and narrative and voice of—wait for it—poems! (I’m a fiction writer.) Reading Ondaatje completely shattered my expectations of what a poem or a novel could or should be doing. Engaging with those poems was odd in the most refreshing of ways—if you, dear reader, have any other suggested readings along these lines, please deposit them in the comment box below with my thanks and a warm hug of gratitude.

My discovery of these poems is an anecdote unto itself: I found a few photocopied excerpts in my mailbox, unbidden, unadorned with note or explanation. They simply existed, a gift from Literary-Santa. I read them and I’m better for it. These are guerrilla tactics, and therefore my project for you:

1.Photocopy excerpts from a work you enjoy, love, can’t stop swooning over.

2.Place them in random mailboxes in your neighborhood or place of work.

3.Live your life.

4.Bask in the knowledge that somewhere, at some time, someone may/will encounter a work they might not have if not for your intervention. Sleep well knowing you’ve planted some seeds, brought the green.

Those are only two examples of the many others I haven’t or won’t name (Maggie Nelson, Ted Chiang, Charles Yu, Eula Biss, Rivka Galchen, W. G. Sebald, Nell Stevens, etc.), yet the idea for which I’m desperately grasping is that a work should stand on its own merits, that it asks questions of me in the most unique ways, gives all of itself to bring forth all of me, scratches those hard-to-reach artistic itches. We can call this style of writing fresh, or genre-defying, or hybrid, or contemporary, or real. We can call these works outliers that stand beside—not replacement-of or inferior-to—traditional narratives that have and will continue to nourish readers. We can call them raspberry berets if we’ve been listening to Prince on a twenty-hour loop. Ultimately it doesn’t matter, as long as a work gives us something we didn’t know we needed in a vehicle we could have never imagined. I’ll call them odd, and embrace it.