Book Review

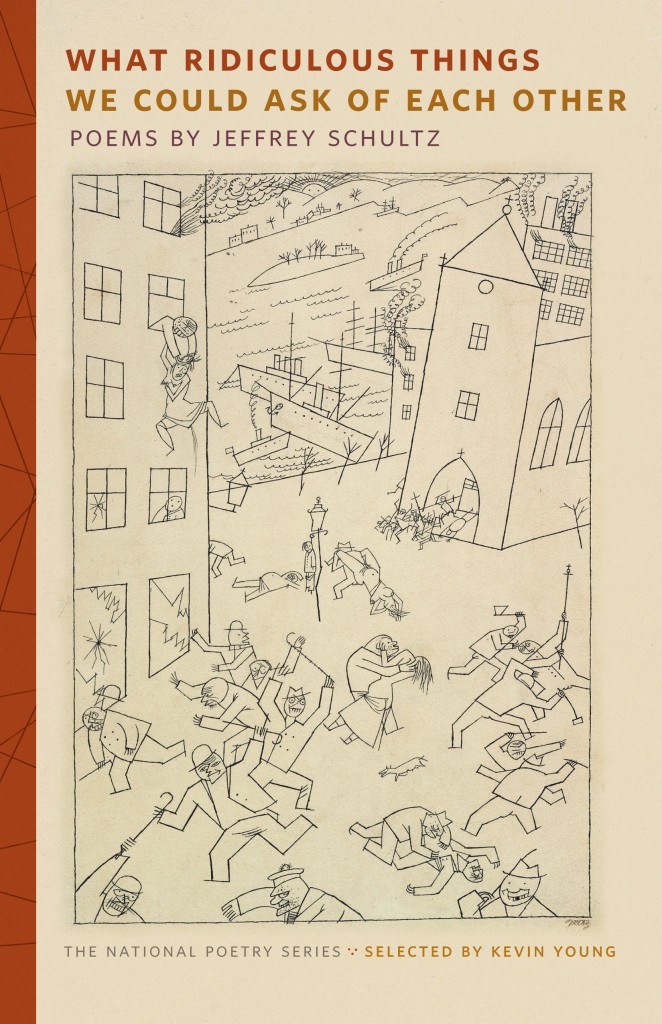

On the cover of Jeffrey Schultz’s What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other, part of The National Poetry Series, you’ll find George Grosz’s drawing “Riot of the Madmen.” In the drawing, jaunty figures run grinning through ordinary streets, attacking one another with axes and bludgeons. Factories bellow smoke, houses are gutted by fire, and ships collide at impossible angles while, in the background, the sun looks down with a comically and horrifically childlike face. It’s a perfect cover for Schultz’s book, which shows a rare gift for finding the horror and the humor underpinning the everyday. Take “The Soul as Social Service Caseworker,” which opens:

The two-way-mirrored visitation room’s empty at last,

and she’s beat. A full hour the Liver and the Will argued,

Unwilling each to understand the other’s point of view.

Swollen and belligerent, the Liver demands sole

Custody; the Will, little brat, has counterpetitioned

for emancipation. It goes nowhere. It seems always

To go nowhere . . .

The everyday reality of bureaucracy and litigation has permeated everything: it has become the lens through which even the old ideas of the Self (with its passions rooted in the liver) must be viewed. Though we can still speak of the soul, we must also speak of “sole custody.” The quest for self-knowledge is reduced to a comically bleak exercise in legal procedure. Meanwhile, two empty cars wait in the parking lot,

. . . their once good-hearted

owners having vanished as so many before into the archives

In search of the one case history which would illuminate

all others. Sometimes they’re found wandering bile ducts,

Dazed; sometimes not. Only Memory, a department decimated

by budget cuts, has a backlog deeper than hers…

As the poem closes, we learn that the Soul’s cubicle walls, hidden behind vast stacks of files, are covered in “clipped // Comics, print-outs of funny email forwards, kids’ painted / pictures, the small things that make life at all bearable.”

Here another of Schultz’s gifts is on display: his talent for catch-22s. Life, we learn, can be made bearable—but the things that make it bearable are so trivial that in fact they make it seem even bleaker. These items are pieces of art—writing, painting, drawing—so, on one hand, perhaps art offers us some respite, some meaning. But on the other hand, the art we’re given here is newspaper comics and email forwards—exactly the kind of mechanically-reproduced mass-cultural products we’d expect to find pinned to every identical cubicle in this bleakly bureaucratic universe. Even the kids’ painted pictures are depersonalized (which kid? pictures of what?). Furthermore, kids are exactly what the parties in this metaphorical custody hearing have been fighting about. Thus even the “small things that make life at all bearable” are implicated in, infected by, the unbearable universe from which they ostensibly rescue us.

Many of Schultz’s best poems follow the strategy of “The Soul as Social Service Caseworker”: they establish a figure and then develop it further and further, comically overextending it, without reminding us that it is in fact only a metaphor. The world of the metaphor becomes more real than what it is meant to illuminate: the caseworker is more realized, more “real,” than the soul.

For another example, take “Apocalypse When?”: The speaker has just realized that the end of days is upon him, belatedly noticing that “Sure, in hindsight, / there was the plague’s sea of fly-specked orphans, / Trails of dead endless in every direction, whole continents / turned the color of sand. But it was all so distant . . .” Now, the looming apocalypse is stalled not by any kind of benevolent and glorious divine intervention, but the squabbling of Hell’s politicos:

A byline: Senators Filibuster in Lowest Chamber of Hell. The debate,

it seems, has been going on for ages, and this is nothing

But the latest default extension of current laissez-faire policies

until some solution’s found for this wholly unprecedented flood

Of immigrants anticipated from above. Some call for containment:

a wall constructed from the surplus femurs of children honed

To a razor’s edge, a moat of serpent infested and boiling blood.

Others push for a limited-integration jobs program, work that’s done

Out of sight. The furnaces, after all, must be stoked, and someone’s

got to collect the bristles of the Beast so that the organ meats

Of CEOs might be scrubbed raw.

Humor and horror: as funny as this vision of hell may be, the notion that precisely the same grand stupidity that rules over our world also rules over the next is far more frightening than any moat of blood. Appropriately, what saves us from all-out Armageddon is equally senseless: “for now, the sticking point’s / a simple question of procedure, and, wouldn’t you know, // Along with the other books, Robert’s Rules of Order has been burned. / This could take eternities . . .”

For all his cynicism, though, Schultz has a moving sense of love and desire for the very world he mocks. The book’s opening poem embodies this ambivalence well, announcing it from the title: “J. Begins by Saying The World’s Not as It Should Be,” implying both outrage and a desire to heal. The poem then opens:

And then, embarrassed at the conversation’s sudden death,

all eyes at once on him, and daunted, honestly, at the prospect

Of going on, of cataloging, in detail, the slow distension

each child’s belly must endure, and each piece of flesh

Cauterized without knowing it would be, without any time

to prepare before the glowing hot shrapnel enters it

And passes through—not, certainly, that preparation

would help in any way—he raises his glass back to his lips . . .

The speaker is angered by the injustice of the world, but offers no solutions. Indeed, he recognizes that even what he thinks he wants, time to prepare, would be no help at all. All he can do is keep drinking. The speaker is equally distraught by the “self-checkout lane’s / smudged touch screen and hideously inoffensive thank you / for shopping” and the “Sitcom’s laugh-track, complication, one-liner, cheap resolution,” that is, by the dreadful ordinariness of the everyday.

Though distressed by the world, he also desperately wants some kind of communion with those who inhabit it: “My friends . . . I feel like we never talk anymore, / like keeping in touch, for no good reason, has become / Impossible.” When he speaks of his dream “of a beautiful country, / And both of us were there, and everyone we do and do not know, / and I tell you, I miss that place,” his longing feels wrenchingly genuine.

And therein lies the beauty of Schultz’s work. If he did not love the world so deeply, he could not be so deeply angry with it for its failures, its horrors, or its disappointments. That’s what makes What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other one of the most moving books I’ve read in years: with tenderness, anger, and pathos, Schultz explores our impossibly troubled relationship with the Self and world, “my country, my lost and human country.”

About the Reviewer

J.G. McClure is an MFA candidate at the University of California – Irvine, where he teaches writing and works on Faultline. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in various publications including, most recently, Fourteen Hills and The Southern Poetry Anthology (Texas Review Press). His reviews appear in Green Mountains Review and Cleaver. He is at work on his first book.