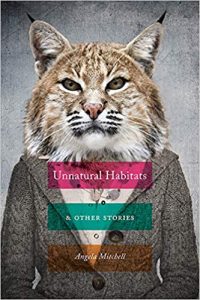

Book Review

In my Introduction to Creative Writing classes, I spend a lot of time talking about the difference between good people and good characters. Good people, I tell my students, are wonderful in real life, but in fiction, they often don’t make for interesting characters. Bad people, on the other hand, tend to make for excellent characters. Unlike in the real world, in fiction we want to see characters make poor decisions and wrangle with the consequences; we want to see their flaws, their blind spots. Of course, as first-time writers, many of my students have a hard time understanding this distinction. Perhaps I’ll have them read Angela Mitchell’s debut collection, Unnatural Habitats and Other Stories, to better illustrate.

In my Introduction to Creative Writing classes, I spend a lot of time talking about the difference between good people and good characters. Good people, I tell my students, are wonderful in real life, but in fiction, they often don’t make for interesting characters. Bad people, on the other hand, tend to make for excellent characters. Unlike in the real world, in fiction we want to see characters make poor decisions and wrangle with the consequences; we want to see their flaws, their blind spots. Of course, as first-time writers, many of my students have a hard time understanding this distinction. Perhaps I’ll have them read Angela Mitchell’s debut collection, Unnatural Habitats and Other Stories, to better illustrate.

What you have here is a collection of loosely connected stories set in northern Arkansas, full of characters motivated, to a large degree, by their own unscrupulousness. They are hardscrabble, morally questionable, and sometimes even violent people. They are also supremely entertaining. Here’s a writer who understands and exploits the sort of ethical inversion that good fiction demands—an inversion in which misdeeds become fodder for effective storytelling.

Mitchell’s collection opens with “Animal Lovers,” a story in which a divorcée tries to settle into a new life, abandoning parts of herself in the process. After this, we meet a host of rich and charming characters: the young girl in “Not From Here” who becomes fixated on a wealthy classmate, the farmer in “Deeds” who discovers that his property is secretly being used for drug production, and the insurance salesman in “Unnatural Habitats” who struggles to find common ground with his teenage son. Each character is rendered with brutal honesty; Mitchell isn’t as interested in making them sympathetic as she is in making them realistic. There is no pandering to the reader’s comfort, as evidenced in “Retreat” when we are told, in regard to a character’s decision to adopt a dog, that “[p]eople didn’t have the money to buy purebreds like they did before, so it was give it away or take a hammer to its head.” Indeed, these opposing extremes seem to embody the worldview of Mitchell’s characters: there is rarely any middle ground, and to lament this fact is a waste of time. The characters are too busy sabotaging themselves, and watching them do so is great fun. The resulting tone is both sardonically comical and mournfully honest, keeping with the Southern Gothic literary tradition from which this collection was born.

One of the common factors between these stories is the setting: Arkansas become its own kind of character throughout the course of the book, its presence looming over the characters’ decisions. Whether characters are chasing after get-rich-quick schemes, dealing drugs, or robbing banks, everything is informed by their environment which, like them, is often wild, dangerous, but not untamable. Here, the region isn’t just a place, it is a state of mind—one that might be inscrutable to people from other areas. Consider this passage from “Pyramid Schemes”:

Tonya had read an article in the local paper that explained how newcomers to Arkansas sometimes developed a lung condition linked to the poultry industry. They suffered with asthma and bronchitis and a slew of other maladies, but natives to the area were fine, born, it seemed, with lungs immune to the feather and dander particles that lingered in the air. She would like to see the inside of her own lungs, imagining them lined with flakes of soft, white down, quivering with every breath she took.

The book positions the reader as an outsider, peering into a culture that feels at once foreign and yet oddly familiar. The characters’ capacity for violence is mirrored by the rugged landscape and its lonely grace, as demonstrated in “Deeds” when we are told that Garnet, an aging farmer, had “grown up in the Ozarks . . . in a rocky holler so deep, it stayed shaded and dark most of the day, and the silence there was enough to make you think you were the last man left on earth.” As the late syndicated columnist Molly Ivins upheld, Arkansas is a place with no pretense at all, and the same holds true of the folks in Unnatural Habitats: for all their faults, they are refreshingly free of artifice.

But Mitchell doesn’t want to sell us on the virtues of the Ozark region; she wants to demonstrate the complexity of these people, for better or worse. And those complexities run deep, as does the author’s psychological understanding that allows her to portray her characters as masses of contradictions, often working against their own self-interest Consider our main character, Dee, and her ex-husband in “Animal People”:

“I don’t know why we have sex like we do. We don’t even like each other.”

“I still like you.”

“You shouldn’t, though,” she said. “It’s not normal. And this sex isn’t normal,

either.

Carter put the magazine down and tipped his head back to look at the ceiling, pausing to think. “Maybe it’s sort of like storing up for the winter,” he finally said. “Maybe it’s like we know we probably won’t be getting it much for a while, so we’re just getting what we can now before it’s too late.”

To say that Mitchell’s characters are unhappy might be a step too far. Instead, the notion of happiness itself becomes questionable. What matters more is that these characters’ ugliness masks a greater beauty that permeates the collection, and perhaps more than most authors, Mitchell understands how easy it is to conflate the two. It’s not that she wants us to abandon our ethical beliefs completely, but she does want us to interrogate them, to recognize that “good” and “bad” people might not be as dissimilar as we think.

I suspect that my students would struggle with Unnatural Habitats for the stories’ refusal to serve tidy resolutions and for the leisurely pace at which they unfurl. However, I have to imagine that they would ultimately come around to it—if not for the vibrancy of the prose, then for the audaciousness of the characters. Mitchell is a gifted storyteller who offers glimpses of her characters at their most vulnerable and most vicious. As a result, it’s impossible not to identify with them, and it is even more impossible not to like them. This is a bold and well-crafted debut.

About the Reviewer

Jeremy Griffin is the author two short fiction collections: A Last Resort for Desperate People (SFASU Press) and Oceanography (Orison Books). His work has appeared in journals such as the Alaska Quarterly Review, the Indiana Review, and Shenandoah. He teaches at Coastal Carolina University, where he serves as the faculty fiction editor of Waccamaw: a Journal of Contemporary Literature. He can be reached at griffinjeremy.com.