Book Review

If I mix a little fiction with my nonfiction, a little lie with the truth, it’s by way of making the truth even truer.

–Peter Selgin, The Inventors

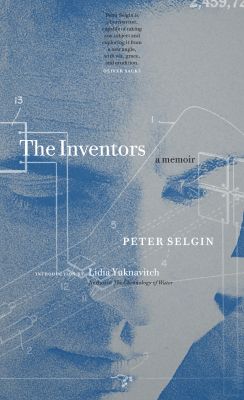

I want to call this book, The Inventors by Peter Selgin, The Book of Home Runs. To write a memoir is—on the surface—to undertake a contrasting examination of both the profound and banal of one’s life and cobble together a sort of meaning out of it. It is a rare human being who can execute this introspective art with a balance of openness and self-scrutiny that invites readers to participate, with full awareness that they may come away with a different conclusion. Selgin delivers that unqualified openness in his story about his inventor father, whom he knew very little about—despite having spent so much time together—and a teacher with whom he had an unusually close bond—a bond that at times bordered on inappropriate.

I want to call this book, The Inventors by Peter Selgin, The Book of Home Runs. To write a memoir is—on the surface—to undertake a contrasting examination of both the profound and banal of one’s life and cobble together a sort of meaning out of it. It is a rare human being who can execute this introspective art with a balance of openness and self-scrutiny that invites readers to participate, with full awareness that they may come away with a different conclusion. Selgin delivers that unqualified openness in his story about his inventor father, whom he knew very little about—despite having spent so much time together—and a teacher with whom he had an unusually close bond—a bond that at times bordered on inappropriate.

I want to call this book The Book of Home Runs for its fascinating use of second-person point-of-view. In an effective and refreshing twist on adult retrospective, Selgin writes not about but to his younger self, pointing out what the boy wouldn’t have grasped in the moment, what his older self has learned, and where his boyish self has simply disappointed him. The perspective might feel harsh if we didn’t each engage in similar acts of self-scorn. These second-person passages, of which the book is primarily composed, are voyeuristic and haunting in quality. They give the work a feel that is somehow less memoir-ish—a genre with the potential for myopic self-importance. Instead, we experience the intimacy of another man’s private struggle with identity, desire, confusion, and blame as if he is not the one telling us:

That your own sense of failure was inextricably bound up with your father’s made his waning all the more bittersweet to you. If only you could make him see that he hadn’t failed you, that of his dozens of inventions, you alone would survive him; that by your failing alone could he truly fail. How urgently you wanted him to know this—and how much more urgently you yourself needed to believe that you hadn’t and would not fail.

I want to call The Inventors The Book of Home Runs for its brief first-person passages that read like a diary and reveal many things, but perhaps most surprising, how to write a memoir. In Selgin’s honest struggle to tell the story, he reveals just how consistently we invent ourselves—either obliterating the past or re-creating it entirely—in order to make sense of ourselves:

This is what I am trying to write about: how, one way or another, by hook or by crook, often with the help of others, we all invent or reinvent ourselves. My father helped invent me by bringing me into the world, the teacher by bringing me into his cottage and classroom.

I want to call this the Book of Home Runs for its startling compassion toward those who failed the author in ways that shaped who he turned out to be: from his father’s sharp criticism and lack of support for Selgin’s writing, to his mother’s complicity in keeping family secrets, to his teacher’s intentional, if not misguided, exploitation of a boy’s perspective of himself and his future. The process of piecing together the details of these people and their lives—who they were, not just to Selgin, but to themselves—unraveling their lies, has made them fragile. And that fragility invites forgiveness and understanding.

“If I mix a little fiction with my nonfiction, a little lie with the truth, it’s by way of making the truth even truer.” There is an inventor in each of us, creating a narrative of ourselves as we wish to be or how we believe we are. And none of us fails to participate in crafting it. It is here, in the space between the profound and banal, where the lies exist. They are the things missed by youth, difficult to discern, secrets withheld, that make the truth even truer, and the endeavor of memoir worthwhile. Peter Selgin shines a bright, probing light on the invention of self. He has delivered in The Inventors one home run after another, each giving us a deeper understanding of ourselves by attempting to understand others.

About the Reviewer

Heather Sharfeddin is a four-time novelist whose work has earned starred reviews from Kirkus Reviews and Library Journal and has been honored with an Erick Hoffer award and at the New York and San Francisco Book Festivals, as well as the Pacific Northwest Book Sellers Association. Her fifth novel, What Keeps You, will be released in September 2016. She has taught creative writing at Randolph-Macon College, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and Linfield College (presently). Sharfeddin holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and a PhD in Creative Writing from Bath Spa University (Bath, England).