Book Review

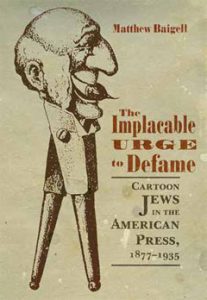

In this timely book, Matthew Baigell examines cartoon images of Jews published in mainstream American magazines in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Among the pages of such popular magazines as Puck, Life, Judge, and Judge’s Library, Baigell examines and interprets anti-Semitic cartoons that are shocking for both their “sheer quantity” and the virulence of their hate.

In this timely book, Matthew Baigell examines cartoon images of Jews published in mainstream American magazines in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Among the pages of such popular magazines as Puck, Life, Judge, and Judge’s Library, Baigell examines and interprets anti-Semitic cartoons that are shocking for both their “sheer quantity” and the virulence of their hate.

Like other minority groups at the time, Jews were subject to nativist fear and hatred. Popular magazines took a dim view of immigrants, and the cartoons reflect this attitude. The cartoonists exhibit a uniform “Anglo-Saxon-based aversion to all minority groups.” Baigell explains:

Cartoons became the major visual medium to dehumanize and discredit American minorities, to caricature stereotypical behavior patterns, and to reduce all those in the line of fire to creatures not fully qualified to become decent, responsible citizens of the country.

But Baigell insists that no immigrant or minority group bore as many stereotypes as Jewish people, showing how they were portrayed as “money-hungry Shylocks and thieving Fagins, social climbers, arsonists ready to claim insurance for property loss, and disagreeable, scheming parvenus who would take advantage of any situation in which they found themselves.” And Jews, despite their small numbers, “were also thought to be organized to take over global commercial and financial markets.”

Baigell describes how Jews were the embodiment of the insecurity of white, mainstream Americans, and functioned as “the quintessential Other, the most unalike and unlikeable among the Others, whose values and goals differed from those of the majority culture.” Jews were “the most Other of the Others,” and their caricatured images reflect this all-purpose hatred.

Baigell scrutinizes dozens of cartoons. In nearly all, one does not even need to read the caption to tell who is a Jew “because they were easily identified by the size of their noses.” Baigel remarks that he “cannot recall a single cartoon in which a Jewish person is not given a bulbous nose.” Jews were represented as demonstrating rapacious business practices, even burning their businesses to the ground for the insurance money. In one cartoon from 1900, a Jewish man with a prominent nose inquires of an Irish doorman (himself caricatured with simian facial features) whether “Ibestein and Rosenbaum are in this building?” The doorman answers in an exaggerated Irish accent: “No – this is a foire-proof building.”

Cartoon Jews will commit any kind of crime for money, yet once they amass that wealth, they are characterized as stingy. Paradoxically, other cartoons stress their extravagant expenses. In one cartoon from 1912, Jews surround an inn called “Cohenhurst Manor” dressed in all manner of ostentatious garments, and carrying status symbols like tennis rackets and golf clubs, which they do not know how to use.

Cartoon Jews also sought world domination. One cartoon called “The English Octopus” places the head of an octopus over the map of England with the name “Rothschild,” the Jewish banking family, in gold letters. From this head, dozens of tentacles spread out to all points of the globe. Jewish capital, the cartoon explains, dominates the world even as it strangles it. New York City, America’s most populous Jewish city, also bore the brunt of cartoonist scorn. In a 1906 cartoon called “Broadway on a Jewish Holiday,” a plump police officer yawns as he leans against a light post. The street is empty; the only clues of the Jewish nature of the neighborhood are signs mocking Jewish occupations like “Diamonds and Collar Buttons” and ugly riffs of Jewish names on business signs, like Hogbaum, Putz, and Piddelwitz.

Baigell explores how some Jewish people fought back against this xenophobia and hatred that was depicted in the popular press. In 1913, the Anti-Defamation League was founded in part as an organization to counter anti-Semitism in American newspapers and periodicals. Jewish people also started their own magazines. Baigell provides many positive images of Jews from these magazines, such as the drawings of Jacob Epstein, who depicted Jewish people at work, study, and in family settings devoid of stereotype and bias.

In Baigell’s concluding chapters, he examines the underlying causes of anti-Semitic cartoons during this time period. He attempts to explain and contextualize the cartoons. For one, he states that the fixation on Jews as capitalists and hucksters illustrates fear of a challenge “to American social and economic structures.” Anti-Semitism is “an amalgam of attitudes, conduct, and ideology” that changes according to the needs of the time. At the turn of the century, anti-Semitic cartoons “helped non-Jewish Americans define themselves as good, decent people rather than as persons committed to enriching themselves in sometimes underhanded (read: Jewish) ways.” The implacable urge to defame is driven, according to Baigell, by “nativist rage.”

The fact that anti-Semitism abated in America before and after the Second World War does not mean that nativist rage has entirely subsided. Recent events have proven otherwise, and the social forces that propel Jews and other minority groups toward marginalization continue to exist—and even to thrive. In our multicultural society, many groups are candidates for defamation. But Jews seem to be repeatedly singled out as a convenient target in the arena of hatred. Baigell’s fascinating book shows how racial hatred in America may be dormant for a time, but continues to fester under the surface of our national landscape–and can reemerge virulently.

About the Reviewer

Eric Maroney has published two books of nonfiction and numerous short stories. He has an MA in philosophy from Boston University. He lives in Trumansburg, New York, with his wife and two children. His book of nonfiction prose, fiction, and poetry, The Torah Sutras, will be published by Albion-Andalus Books in 2018.