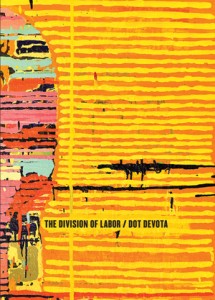

Book Review

Dot Devota’s newest collection of poems, The Division of Labor, is a difficult and beautiful work. That seems too easily said, and maybe said overly much about works of poetry and artistic endeavors at large. What is more important is that this collection reminds us why some works of art must be difficult. The book seamlessly weaves through stuttering pastiche and sudden, necessary lyric—it is a book that interrupts itself to acknowledge its own shortcomings, its own insufficient tool. Language and its logics break in the mind, as much as they do on the tongue.

Though the book isn’t entirely maximalist, it does dwell in the world of multitudes, of the possible and impossible being flushed out nearly to the point of exhaustion. It is ambitious in its range and in its words. Its mission isn’t always clear, but it is a work that reaches and is wonderful in its reaching. The world caves in on itself and a hand reaches from the poems to pull you back out and gives eyes to look back upon the rubble it has created:

Sometimes we can be a two-headed

beast ruining a fairytale. We share the same heart—a

muscle used to lift the world up off us.

This book is attentive, and in its attention exposes both the savory and unsavory. It is a pleasure to read, but the pleasure is complicated. In fact, pleasure itself becomes a question of the work, which touches on topics like the Abyss, the Apocalypse, History, Tradition, Future, Logic, Philosophy, Intimacy, Self/Other, Patriarchy, Religion, and Nature.

The Division of Labor operates in a world of self-compartmentalizing: how else does the body operate in this physical world? This compartmentalizing is itself a formal quality of the book. It is divided into sections and these sections become formal representations of the body and mind operating in the language/body/text. The book opens with a recurring section called “Topic Sentences” composed entirely of found text which read as individual thoughts, notes for later truths one hopes to get to, a revelation half concealed. We garner some sinew to pull through these fragments, to make meaning from the world, the texts that have already tried to claim it. Our work, surely, is not finished:

There is in this universe no reason, therefore, to imagine the end . . . He attacks both . . . The problem of the seizure . . . Under the easy predictable pressure . . . There is a moment’s doubt . . . The cynical intervention . . . While waiting to dominate space . . . How rapid will be the development . . .

Here Devota unsparingly shows us something of the human condition—the world filled to the brim with information, yet somehow still feeling empty, foretelling the foreboding, or at times, one hopes, the hopeful. Yes, even the abyss has some life in it. It is that glint of feathering weary life that makes it more unbearable than anything “absolute.” Nothing is ever enough; it is already too much. We live in a very real world, and Devota reminds us it is a world of paradox and danger. The bankrupt bank is garish because the lights are still on, the teller still smiles at you, tellingly. It is a world, maybe only convinced (by itself), that it is constantly approaching realization, finally, at last—but Devota masterfully denies any sense of closure. Instead, we are given a world that continuously opens and asks questions—both of us and of itself, the supposedly immutable universe. Devota does what great artists do: she clutches at her tools, she interrogates her mind, she interrupts herself.

In one of the many poems called “The Eternal Wall” Devota writes:

The world is later than we think –

crowded, understaffed. The impenetrable

lives alone in full conclusions. Scared to be

honest out loud I’m kept at rope’s length

knotting the present.

Language feels insufficient. Poetry’s endless attempt to capture the now, to slow time and stall the world, is impossible and so we write it, again and again. “The Eternal Wall” is rote, written again, repeated because it is never complete. It never says what it means to say in fullness. It’s as though Devota’s poems call out, “No, let me do what I had set out to do,” only to look back upon themselves and realize what they had said was only a fragment—an instance of its own accord, not enveloping the impossible world.

Trying to tame the world for our art is destined for some degree of failure, yet it yields moments of true beauty—the kind of beauty that is revealed in accident and attention. Dot Devota’s work does exactly this:

When the future became present

you were all adopted. To tread its wilderness

I love the ways in which the found text is cut through with these shorter lyrical intrusions. It gives more life to the pastiche of “Topic Sentences”—though as I say this, it seems oddly reductive to call it “pastiche,” as though to say so means that “Topic Sentences” serve only as a nod to some postmodern condition that condemns the reader to a gluttonous meal of meaningless intellectualism and perpetual forgetting. I’ve struggled for some time to think of what I want to say about these particular sections. What do they do? In many ways, I hesitate to write anything about them, I want to sit and be quiet. I want to absorb the landscape that is being created out of what has already been seen. I will say that these passages feel wonderfully blank to me—as a landscape often can. What has been said of the world isn’t enough. Devota knows that words do not heal wounds. Her book is an attempt to wave a light in the fog so that one can, at last, after God-knows-what journey, orient oneself.

The Division of Labor is not in defense of the world grown sour on itself. It is not offering a remedy for humanity’s illnesses. It acknowledges beauty, even revels in it, but knows that beauty, too, can be but a passing symptom, a fever dream that flees our mind and body. Devota reminds us that it is not our duty to speak of the world’s wrongdoings. Yes, “I spit.” And yes, “Every time I cry it is / to break the human vase arranging No’s silence.”

This is also a book of historicity. We cannot separate ourselves from the terrors and maladies of civilization. I’d like to think we are born free. Free and wild. We are young and wondrous but suddenly, horrifically, historically, we find ourselves “with orders to kill.” Devota’s language takes on a method of conflating the assumed binaries of natural/unnatural:

No one breathed. The body of water was

a crescent wave keeping scholarship, beckoning

snails to get off their land mass

hurry like tanks, liberty’s mollusk. Behind me, you

entire Polynesian islands

sank forming the simplest anniversary.

In doing so, we reckon the artificiality of the divisions imposed through our language. We are animal and robot. We are me and you. Devota does a great service in pressing and breaking the coded classes of language we stick to. In this book we cannot be only an academic, only an activist, only a murderer, only a soldier, only a pacifist, only a sinner, only pious. We are irrevocably us, which, as we see in Devota’s words, is a complicated network existing in the temporal, uttering out words, committing acts, abandoning to abandon—“I vow / to be the border / of two warring countries / called home.”

Often in this work we are thrown back to a trope of origin: the sea. In “The Burning of Past Spaciousness” she writes, “Faraway fires / fluttering embers out to sea.” There is something here of death and rebirth. The fires of destruction produce things that find their way back to the sea—the sea where the book begins, where life began. There is optimism in this book, but it is an optimism like none I’ve otherwise encountered—it is one that does not say “all will be fixed”; it is one that says we will, at least, forever be able to begin again. We may invent our own language anew out of the corpse of our past. We can rebuild. We can learn to speak again. This is an optimism I want to live.

About the Reviewer

Grant Souders is the author of the chapbook, Relative Yard (Patient Sounds, 2011), and a collaborative book with Nathaniel Whitcomb and Matthew Sage, A Singular Continent (Palaver Press, 2014). In 2014, he joined Matthew Sage in editing Patient Presses, Intl., including their chapbook series and their quarterly, digital magazine, WINDOW. Recently, his poetry has appeared in the Boston Review, jubilat, iO, OmniVerse, Denver Quarterly, and other venues. His first full-length collection, Service, is forthcoming in the Spring of 2017 from Tupelo Press. His visual art can be seen at grantsouders.com. He received his MFA from the University of Iowa’s Writers Workshop where he was a Maytag Fellow. He currently lives in Denver, Colorado.