Book Review

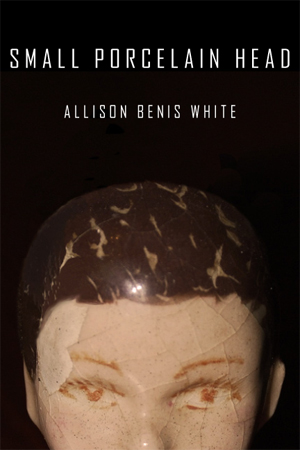

In Allison Benis White’s stunning second collection, Small Porcelain Head, commonplace domestic objects serve as points of entry to compelling philosophical questions: To what extent is childhood permeated by loss? How do everyday items—a child’s doll, a pair of scissors, a dress—teach us our first lessons about life and death, temporality and impermanence? Can one ever fully recover from these realizations? As White explores possible answers to these questions, even her smallest stylistic decisions illuminate and complicate the text itself. The end result is a beautifully crafted book that lends itself to rereading, and poems that reward careful attention.

In Allison Benis White’s stunning second collection, Small Porcelain Head, commonplace domestic objects serve as points of entry to compelling philosophical questions: To what extent is childhood permeated by loss? How do everyday items—a child’s doll, a pair of scissors, a dress—teach us our first lessons about life and death, temporality and impermanence? Can one ever fully recover from these realizations? As White explores possible answers to these questions, even her smallest stylistic decisions illuminate and complicate the text itself. The end result is a beautifully crafted book that lends itself to rereading, and poems that reward careful attention.

White revisits a few carefully chosen imagistic motifs as the book unfolds, a choice that lends unity to the sequence as a whole. Perhaps more importantly, these objects are inscribed with wide-ranging emotional significance, which allows them to acquire complex histories that seem at once vast and neatly contained. It is this fascination with the psychic weight we attach to objects that makes White’s poetry so compelling. She is able to offer profound insights about the nature of grief, all of which remain grounded in the tangible details of our everyday existence. Consider this passage:

What is left but obsession, handling the object over and over? My hands fit

around her waist.

Unbuttoning, I wanted nothing to happen or the same thing to happen forever

in the same place.

Although it is better, it is impossible to miss one thing or when you go,

to miss yourself.

Here White imbues commonplace domestic objects with philosophical significance, particularly as she uses a child’s doll as a point of entry to a compelling discussion of temporality. The act of “handling the object over and over” teaches the speaker of the poem about the nature of permanence and impermanence, mortality and its inevitability. The object’s permanence, its ability to endure throughout time, is what renders it lifeless, inert. The fact that White’s metaphysical observations are carefully grounded in physical details—the speaker’s tiny hands “around the doll’s waist,” the buttons on its dress, etc.— renders her meditations all the more profound. The reader is able to see how these abstract ideas relate to the world around her, even as White dazzles with her apt choice of imagery and expert technical decisions.

With that in mind, White’s attention to detail while offering abstract discussions of time, grief, and mortality is truly stunning. Presented in prose vignettes, the book creates a readerly expectation of wholeness, a coherent narrative, and a sense of resolution, which the poet works to undermine. Though offering the visual impression of intactness, the narrative is actually fragmented, shattered. It is this discontinuity between form and content that renders the work so profound. Just as a grief stricken child often gives the appearance of innocence, happiness, and cheer while suffering, the poems themselves enact this disconnect between one’s inner life and the persona that one presents to the world. White explains:

That she has the right to turn the room inward. That when I speak, ashes flutter

from my mouth.

That her hands are drawn in lipstick on the mirror, two firecrackers. That her

hands are gone.

I cannot go any further with my mind. That my mind is a hole, when it flickers,

means bang.

In passages like this one, White constructs the appearance of a coherent narrative, complete with paragraph breaks and meticulous punctuation. But within this pristine prose, one encounters a poignant fragmentation of meaning. Readers find only pieces of a story, which they must work to reconstruct, in much the same way that a grieving individual would attempt to create meaning through narrative. Readers are asked to enact the grieving process alongside the speaker of the poem, particularly as White prompts them to actively speculate and assign meaning to the shards with which they are presented. Small Porcelain Head is filled with beautifully crafted poems like this one, which offer a thought-provoking relationship between form and content, dazzling the reader with visually arresting imagery all the while. In short, White’s latest collection is a finely crafted book, and a truly spectacular addition to this gifted writer’s body of work.

About the Reviewer

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of fifteen books, which include Melancholia (An Essay) (Ravenna Press, 2012), Petrarchan (BlazeVOX Books, 2013), and a forthcoming hybrid genre collection called Fortress (Sundress Publications, 2014). Her awards include fellowships from Yaddo, the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, and the Hawthornden Castle International Retreat for Writers, as well as grants from the Kittredge Fund and the Elizabeth George Foundation. She is currently working toward a Ph.D. in Poetics at S.U.N.Y.-Buffalo.