Book Review

After enough time, life becomes utterly baffling. Making sense of the past and how one has arrived at this particular moment, now, becomes an exercise of mounting futility with each successive year. The objects one lives with and life itself begin to take on abstract qualities. A balled up T-shirt on the floor becomes a symbol of mystery. Where did it come from? Who bought that for me? Meanwhile, major and minor concerns—the births, jobs, marriages, and deaths—make their entrance and set us on a new course. They distort the past, making it viewable only at an angle. Was that my life? Really? Rather than focusing on the unobservable and elusive nature of lived experience, Karen Leona Anderson has found a novel way to capture these mysteries and set them in clear light: the poems in Receipt are sourced from receipts and recipes. In Anderson’s skillful hands, these mundane documents reveal the essential and devastating truths about the incompleteness of our lives. Recipes and purchases, material and immaterial, become evidence of our failed attempts to cobble together a unified whole: a splendid meal, a well-decorated home, a diverse wardrobe, a happy family. Rather than mourning our failures, though, Anderson’s poems insist upon the desires that precede them, lending a matter-of-factness to our personal wagers on the future.

Anderson addresses her own project most straightforwardly in “Can-Opener Cookbook,” writing, “Everyone has some / trashclass taste, some / Hi Lo Cookie hook, / and what’s his?” Questions of taste and sophistication are prevalent throughout Receipt, but this poem most directly reckons with establishing meaning through such traditionally “low” cultural icons like cookbooks. In “Hollywood Dunk,” she sources the 1956 Betty Crocker Picture Cookbook to grapple with the demands put on women, the “almost- / married Americans, deviled hams dressed up, / mid-chickflick.” The motifs of mid-century womanhood, through their recurrence, lose their wistful glow and instead become blanched, lifeless signifiers. Even in their death, though, they assert their power in altering one’s own self-image, most succinctly demonstrated in the lines:

I need to fit

in that satin dress? I need to say what? If I

had coated myself in cream, my in-laws say,

I’d like me better.

In “Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air,” the narrator is “beaten by the recipe” while listening to a radio show for “directions on how to stay newly wed.” What is especially striking in this poem, as in others throughout the collection, is its emphasis on desire. Anderson gives her speakers agency through their desire to be better wives and mothers, especially in an era where there was little room to become more. Rather than satirizing this period, she redeems the housewife figure, who is, in the poem “Ladies Night,” now a “goddess at last by virtue / of the bulk bin” who declares with her worn maxim, “it’s easy to raise myself up / from my sad past.”

The poems in Receipt contain a barbed energy that recall the demented curl of a Gary Lutz sentence. Anderson’s language unwinds with a staggering lucidity before arriving at a startlingly clear image. She does so in “So, Nature,” writing, “Uncobbled / from the quadrupeds, now my own horse, condo’d / and mobile enough, I guess, hobbled to my car, silver in the garage, pretty close to my neighbor’s.” Her pacing is subdued and infectious, and it will get under your skin. These poems’ peculiar energy becomes most apparent when they are read aloud. “First House” is equally invested in the ear as in the mouth:

A dead junco is a grey feather boa, strong on the bush.

Its head is a hawked black hole in my imagined mortgage

and warred-for mornings.

Just as Anderson’s teetering poetry signifies movement, it also embodies it, making the reading of Receipt an entirely visceral collection that will pleasantly work your jawbone.

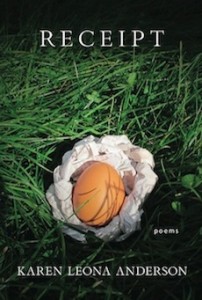

On the front cover of this book, a single brown egg rests precariously in a crumpled up receipt. This image mirrors perfectly the precipice-gazing anxiety that runs through much of Receipt. In “Meringue ($3.25 Patisserie Belge),” Anderson inserts pockets of space into the poem as a baker would beat air into egg whites, though the result is less confection than dread:

everything trembling

on the cusp of breaking debt

fracking me that I stay

elastic.

In an Anderson poem, it is an act of grace to just keep life going for another day. She lends a beauty to the mad activity of our buying and cooking, the times when we have to struggle to keep it together, or, as Anderson beautifully frames it in “Asparagus,” “before the flower / bursts its stem, the rush of green.” After finishing this volume, readers will surely be searching their own pockets for similar moments of wonder and transformation.

For another perspective on Karen Leona Anderson’s Receipt, see Joseph Hall’s review here.

About the Reviewer

Phillip Garland’s fiction has appeared in Parcel, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Red Lightbulbs, and other places. He hails from Tennessee and lives in Chicago.