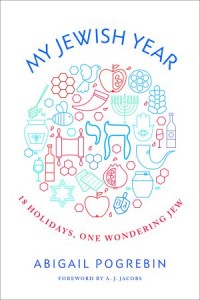

Book Review

Abigail Pogrebin’s My Jewish Year chronicles the author’s yearlong engagement with religious Judaism. At first this venture appears to be possibly unnecessary, as Pogrebin is already enmeshed in New York City’s Jewish life. She attends one of the largest Reform synagogues in the city and frequently writes about Jewish topics in such worthy forums as the Forward.

But despite Porgebin’s social circle, she readily admits that her knowledge of Judaism is sorely lacking. She explains in the introduction: “All I knew was that something tugged at me, telling me there was more to feel than I’d felt, more to understand than I knew . . . I hadn’t graduated much beyond the survey course when it came to Judaism.” Her Jewish religious upbringing was attenuated: “Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Hanukkah, two Passover seders, and the sporadic Friday Shabbat.” These observances, she explains, “are a drop in the bucket compared to the total number of holidays that flood the Jewish calendar.” For years Pogrebin watched orthodox “families adhere to an annual system that organizes and anchors their lives.” And while she did not envy their dogmatic certainty, she aspired to “their literacy.”

She begins her quest with a startling revelation: the High Holidays, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, are not the beginning of the season for self-examination, but the end. For most religious Jews, the month before Rosh Hashanah, Elul, is a preparatory stage for the High Holidays. Pogrebin follows an Elul program, blowing a shofar every morning, reciting psalms, and working on a list of personality traits she would like to improve, one trait for each of the forty days of Elul. She finds a chavruta, or study partner. They both participate in the forty day program, and confer with each other every night, sharing their successes and failures in the task of self-betterment.

Pogrebin, at first wary of Elul’s radical self-examination, grows to love the exercises. Her nightly exchanges with her study partner become “trinkets of candor, which I collect.” As she works her way through the list, and late summer turns to fall, she finds that the “specificity of the list makes self-examination sharper, plainer. There’s less room to skirt the truth.” Elul’s semi-private confessions prepare Pogrebin for the wider, more sweeping activities of the High Holidays.

Pogrebin is particularly intrigued by the six fast days of the Jewish calendar. She does not like fasting, and was not even aware of most of the fasts. Most, like the Fast of Esther, catch her off guard. The Fast of Esther is part of the preparation for Purim, which commemorates what Pogrebin calls “a dark story marked by a crazy party.”

In the Tanakh’s book of Esther, the Jews of Persia are almost slaughtered by Haman, a member of the king’s court. Esther, the king’s wife, who is hiding her Judaism, intervenes and the Jews of Persia are saved. Purim is a raucous holiday. Traditionally, the book of Esther is recited and there is considerable drinking. But before this, religious Jews participate in Esther’s fast. Pogrebin explains, “It must be embroidered on a sampler somewhere: ‘Before they party, they must suffer.’” Esther fasts before unraveling the genocidal plot. Her fast represents the risks of taking the mantle of leadership. And it is through this fast that Pogrebin herself finds the strength to take on a leadership role in her synagogue.

In addition to many small details of Jewish practice, Pogrebin learns about two overarching themes of religious Judaism. First, she explains, “how we behave says a lot more than how we feel.” Judaism demands action. Even if we do not feel generous, the giving of tzedakah, or charity, is demanded by Jewish law. With enough correct behavior, there is the explicit assumption that moral action will lead to moral beliefs. Second, she clearly sees the threads connecting every Jewish holiday. They all commemorate different events, but they are bound through the force of collective Jewish memory, and the natural cycle of the seasons. She says, “the Jewish schedule . . . [reminded] me repeatedly how precarious life is, how impatient our tradition is with complacency, how obligated we are to rescue those with less, how lucky we are to have so much history, so much family, so much food.”

Pogrebin’s journey is distinct and individual, yet one which mirrors the quest of many Jewish people in America. American Jews are setting out in new directions to define what it means to be Jewish. Like them, Pogrebin moves both within and beyond the confines of established denominations of Judaism to find inspiration. Indeed, Pogrebin’s year of wondering leaves an impact on her sense of Jewishness. She explains: “I felt part of something unshakable, unbreakable.” But she does have a number of stipulations: “my religion was amplified, but not my religiosity.” Pogrebin’s understanding of Judaism increases, but her desire to practice the religion does not keep pace. She says, “I feel more prayerful now; but I don’t think I’ll pray more often. My Hebrew is still halting.”

Despite her year of Jewish practice and the widening of her Jewish literacy, Pogrebin is still working to define her Judaism and, specifically, what it means to be a Jew in America. American Jews face difficult challenges, and foremost is the abundance of choice. Like Pogrebin, Jewish people can decide how much of their religion to practice—or not at all. In the face of so much freedom, choices can be daunting. Pogrebin recognizes and shares the challenge and the message: this is a great time to improvise, as seldom have so many options been open to so many Jewish people.

About the Reviewer

Eric Maroney has published two books of nonfiction and numerous short stories. He has an MA in philosophy from Boston University. He lives in Ithaca, New York, with his wife and two children and is currently at work on a book on Jewish religious recluses, a novel, and short stories.