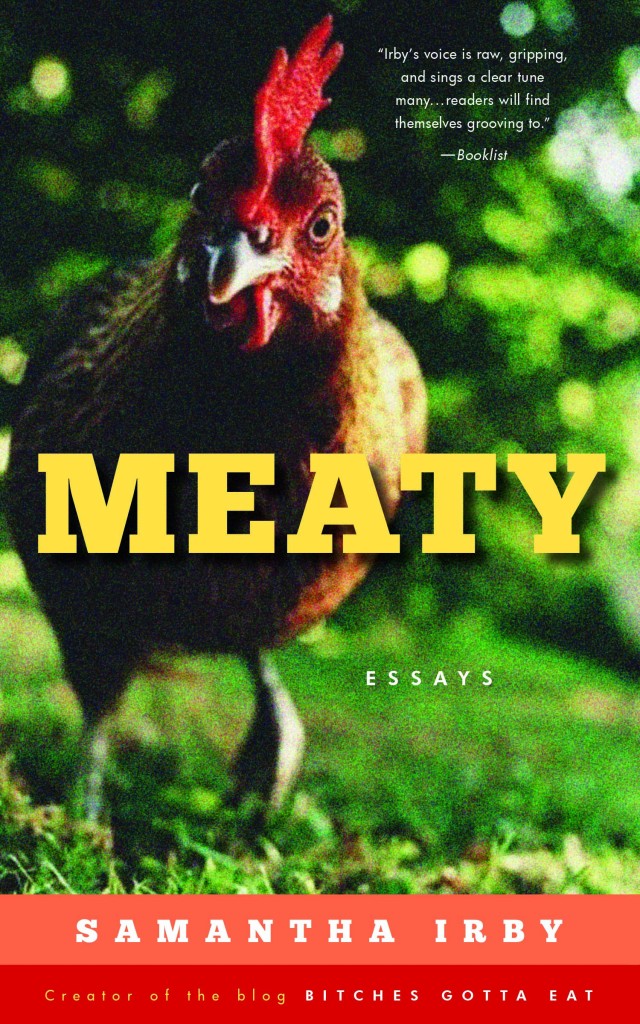

Book Review

Samantha Irby wants to be friends. Or so you imagine as you read her fine new essay collection, Meaty, wherein she shares with you everything only your closest friends would share. The terrors and humiliations of childhood and adolescence. The indelible marks left by poverty and a broken home. The stupidity of dudes who never call, much less remember to bring the occasional bouquet of flowers. The never-ending war fought upon the battleground of the body. The complex banality of sex, the science of chronic diarrhea, the search for love.

Samantha Irby wants to be friends. Or so you imagine as you read her fine new essay collection, Meaty, wherein she shares with you everything only your closest friends would share. The terrors and humiliations of childhood and adolescence. The indelible marks left by poverty and a broken home. The stupidity of dudes who never call, much less remember to bring the occasional bouquet of flowers. The never-ending war fought upon the battleground of the body. The complex banality of sex, the science of chronic diarrhea, the search for love.

The collection—to be released this fall by Curbside Splendor—spans three years of Irby’s life, beginning with her thirtieth birthday and closing with her thirty-third. Her needs and desires, her existential condition, remain pointedly unchanged: “Today, 2/13/10, is my birthday,” she begins in “At 30,” the first essay in the collection. “I am excited because I am 30 years old and I don’t have a man in my life. I haven’t had any children. I haven’t finished college. I don’t have any major accomplishments of note.” The final essay in the collection, “I Should Have a Car with Power Windows by Now,” begins likewise:

Today, 2/13/13, is my birthday. I am excited because I am 33 years old and the idea of a man in my life totally bores me. I don’t have a college degree. I don’t know how to make coffee in a french press. The filter in my humidifier needed to be changed three weeks ago.

These essays that bookend the collection catalog Irby’s hopes and fears, her ambitions and apathy, as well as examine the burden that comes with bearing such fierce contradictions. For instance, Irby claims that “the idea of a man…totally bores” her, but three paragraphs later admits that “I want an artsy dude who is sexy and likes my jokes. I want to hear someone who means it tell me how much he loves me.” True and true and true.

As with other compelling essayists, Irby’s confessions tend to be braver and more honest than any we’ve recently made in public. And funnier. She has Crohn’s disease, an autoimmune disorder that inflames the gastrointestinal tract, causing all manner of unattractive episodes and panic-stricken emergencies that range from day-to-day “spotting,” which necessitates the occasional Depends adult undergarment, to all-expenses-not-paid, week-long hospital stays where she’s permitted to eat vegetable broth, hard-boiled eggs, and dry toast. In “Sorry I Shit on Your Dick,” Irby addresses an open letter to “New Boyfriend,” supplying the rules of the road, as they were. She advises him that at some point:

I am going to grip my middle in a panic and turn desperately to you, begging you to PUT YOUR FOOT ON THE GOD-DAMNED GAS BECAUSE IF YOU DON’T YOU’LL BE CLEANING DIARRHEA OUT OF THE POROUS FABRIC ON YOUR CAR SEAT. Oh, I’m kidding. I’ll clean it. But you will have to stand there watching me, and that is almost equally humiliating. So drive fast. And always be on the lookout for places with public restrooms.

Dudes and romantic relationships figure prominently throughout the collection, providing the thematic trajectory for such essays as “I Really Don’t Eat This Much Salad!”; “Would Dying Alone Really Be So Terrible?”; and “The Terror of Love.” In “A Bearded Gentleman,” which provides the title for the collection, Irby admits that her “perfect man” is a lesbian named Angie Frank who “gets up early and makes her partner a smoothie before she even wakes up,” “walks their dogs during snowstorms,” and “runs and gets the car so we don’t have to stand outside in the rain.” Then she provides an annotated list of characteristics that she looks for in a man: 1. Masculine (“Where are the motherfuckers who smell like whiskey and gasoline?”); 2. Books (“Anything that makes his brain work”); 3. Passport (“I’m tired of dicking around with stunted adolescents”); 4. Patient (“I’m doing this new thing where I try to wait more than half an hour to bang a dude I’m into”); 5. Nice (“I’m talking basic consideration”); and 6. Bearded/Meaty.

This last entry receives no further description because the bearded meatiness of such an ideal man is reflected throughout the collection’s narrative voice (cultivated in the entries of Irby’s popular blog, bitches gotta eat, subtitled “tacos. hot dudes. diarrhea. jams.”). She may be coarse and sometimes shocking (“If you stick your thumb in my asshole again I am probably going to shit on your dick. So don’t do that….You have to order anal sex two days in advance, like peking duck.”), and she may package her experiences to resemble a series of gags and pratfalls, but Irby never stoops to address an unimportant subject. She is in search of the big prizes: love, acceptance, wholeness, peace.

One of the central essays anchoring the collection, “My Mother, My Daughter,” details Irby’s harrowing childhood experience caring for her mother, whose multiple sclerosis is exacerbated by a car crash when Irby is only nine, leaving her mother unable to leave their apartment or conduct day-to-day tasks unaided:

I was expected to keep my fucking shit together, and learn the goddamned state capitals, while terrified that my mom was going to drown in the bathtub while I struggled to grasp the concept of halves and thirds. I didn’t yet understand the difference between God and the President, yet I knew which pills went with breakfast and which ones were taken after dinner.

They move closer to the fire station so that Irby is able to run there for help, because they don’t have enough money for a phone. And though she does run there one night to save her mother’s life, Irby soon after learns that there comes a day for us all when no one can save us.

Irby’s essays are written in defiance of such a day. Relationships may crumble, the electricity may be shut off, jobs may grind us, our bodies may betray us, and bitches may be bitches, but Meaty shows us a way of being in the world that argues wisdom and self-acceptance are monuments built of endurance and perseverance. No matter how lost and afraid we may be when we first regard the imposing hunk of rock that life sets before us, we must learn to shape it into something useful and fulfilling. There will be no revelation unless we swing our hammers, day after day, chipping away at our self-doubt and uncertainty until perhaps something meaty is discovered, something transformative that shows us what we’re made of. Irby claims that she needs a winning lottery ticket, but this collection makes it clear that most of all she just needs to keep on writing.

About the Reviewer

David Bowen is co-founder of New American Press and Mayday Magazine, and a doctoral candidate at University Wisconsin--Milwaukee. His work has appeared previously in such journals as The Literary Review, Flyway, Monkeybicycle, Reconfigurations, and Great Lakes Review. He received his MFA from University North Carolina--Greensboro in 2003.